It’s a story that has transcended cultures and generations. When Wu Cheng’en first penned Journey to the West, he likely never imagined the global phenomenon it would become. From modern Japanese literature to ancient Korean architecture, the legacy of Wu’s 1592 classical work is deeply rooted in Asian mythology, and its influence continues to shape the region’s cultural, philosophical, and religious outlooks.

Today, Journey to the West continues to inspire countless reinterpretations. Among the most recent is the action RPG Black Myth: Wukong, developed by Chinese studio Game Science. The game reimagines the legendary Monkey King in a darker, more cinematic world that draws heavily on the source material’s mythic richness. With its striking visuals, dynamic combat, and clear reverence for the original novel’s spiritual and cultural themes, Black Myth introduces a new generation to the complexities and contradictions that have long defined this epic.

But what is Journey to the West really about? If there’s one certainty, it’s that we’ve got no shortage of adaptations through which to explore the question. At its core, it’s the story of a Buddhist monk, Tang Sanzang (also known as the Longevity Monk), who travels to India with his disciples to retrieve sacred scriptures. A fictionalised retelling of the real-life pilgrimage of Xuanzang during the Tang dynasty, the novel’s filled with fantastical elements: encounters with demons, monsters, and supernatural beings, as well as richly developed backstories for each of Tang’s travelling companions.

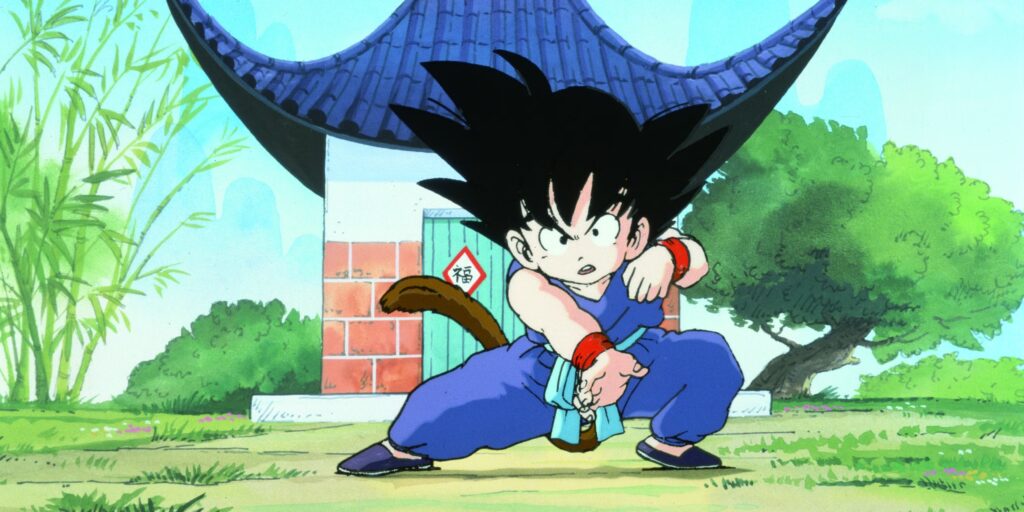

The most famous of these disciples is undoubtedly Sun Wukong, Tang’s first and most capable ally. Often referred to as the Monkey King, Wukong is widely recognised as the face of Journey to the West, and arguably its true protagonist. The story opens through his perspective, and it’s Wukong who experiences the most profound transformation throughout the journey. In many ways, it’s his story we’re truly following.

Regarded as one of the Four Great Classical Novels of Chinese literature, Journey to the West is celebrated for its timeless themes, imaginative worldbuilding, and unforgettable characters. Wukong, once a rebellious and arrogant immortal, is sentenced to serve Tang as penance, restrained by a magical crown that tightens around his head whenever he defies his master’s will. Over time, he evolves into a disciplined and loyal disciple, ultimately earning divine status by the end of the novel. On the surface, it seems like a fitting resolution — harmony restored, enlightenment achieved, and balance between Heaven and Earth re-established.

But that’s not where Wu chose to end the tale.

In the hands of another author, the retrieval of the scriptures and the achievement of spiritual enlightenment might’ve served as a natural conclusion. Yet Wu introduced one final challenge, one that no strength, wit, or perseverance could overcome: humanity itself.

After 18 long years of facing demons, temptations, and spiritual tests, the group finally reached the gates of Heaven, ready to receive the sacred texts destined to enlighten the people of China. But instead of being welcomed, they were stopped by two of the Buddha’s servants, who refused to hand over the scriptures without first receiving payment. The moment shattered any illusion of pure intention. Wukong, outraged, suspected it was a trap. How could such a divine mission end in bureaucracy and bribery?

Wukong went to confront the Great Buddha, demanding an explanation. The Buddha reassured him that it’d all been a test, a final measure of their devotion and humility. Trusting this answer, the disciples returned — only to find the demand for gold waiting for them once again.

Faced with this repetition, the truth became impossible to ignore. Despite all their victories over monsters, their resistance against divine forces, and their endurance across time, they couldn’t conquer one thing: the greed of men. No magic could purify it, no weapon could destroy it, and no scripture could wash it away. The demons they’d faced bore names and faces; human desire didn’t. It was an invisible enemy, cloaked in ritual and sanctity, demanding coin at the gates of salvation. In that moment, Tang and his disciples realised that their greatest obstacle hadn’t been dragons or demons, but the deeply entrenched flaws of the human world they’d set out to save.

In the end, Journey to the West is more than just an adventure filled with gods and monsters. It’s a philosophical meditation on the human condition. Beneath its vibrant mythology lies a sobering insight: the path to enlightenment isn’t only a battle against external evils, but also an internal reckoning with human weakness. Wu uses allegory and satire to show that even the most sacred quests can be compromised by worldly desire. The journey may begin with the hope of transcendence, but its conclusion reminds us that we’re still tethered to greed, ego, and imperfection.

And that may be the story’s most enduring legacy — not just as a beloved myth, but as a mirror reflecting every generation’s struggle toward something greater. Black Myth: Wukong, in reimagining this tale for a modern age, steps into that legacy with both reverence and urgency. Its stunning interpretation of Sun Wukong may feature dazzling visuals and brutal combat, but at its core lies the same question Wu posed centuries ago: are we truly prepared to pay the cost of enlightenment?